Introduction

After experimentation with the previous project at: https://jesse-anderson.github.io/Blog/_site/posts/ESP32_Post_1/ , I encountered issues with the DHT11 sensor maintaining reliable contact with the internal breadboard connections. To address this, I acquired someProtoboards from ElectroCookie and began the process of soldering the components together. I chose ElectroCookie as they were highly rated on Amazon and apparently the Adafruit Protoboards are corrosion prone. It also helps that the ElectroCookie ones were far cheaper! This post details the steps I took to resolve these issues and enhance the project’s overall performance.

Soldering the Components

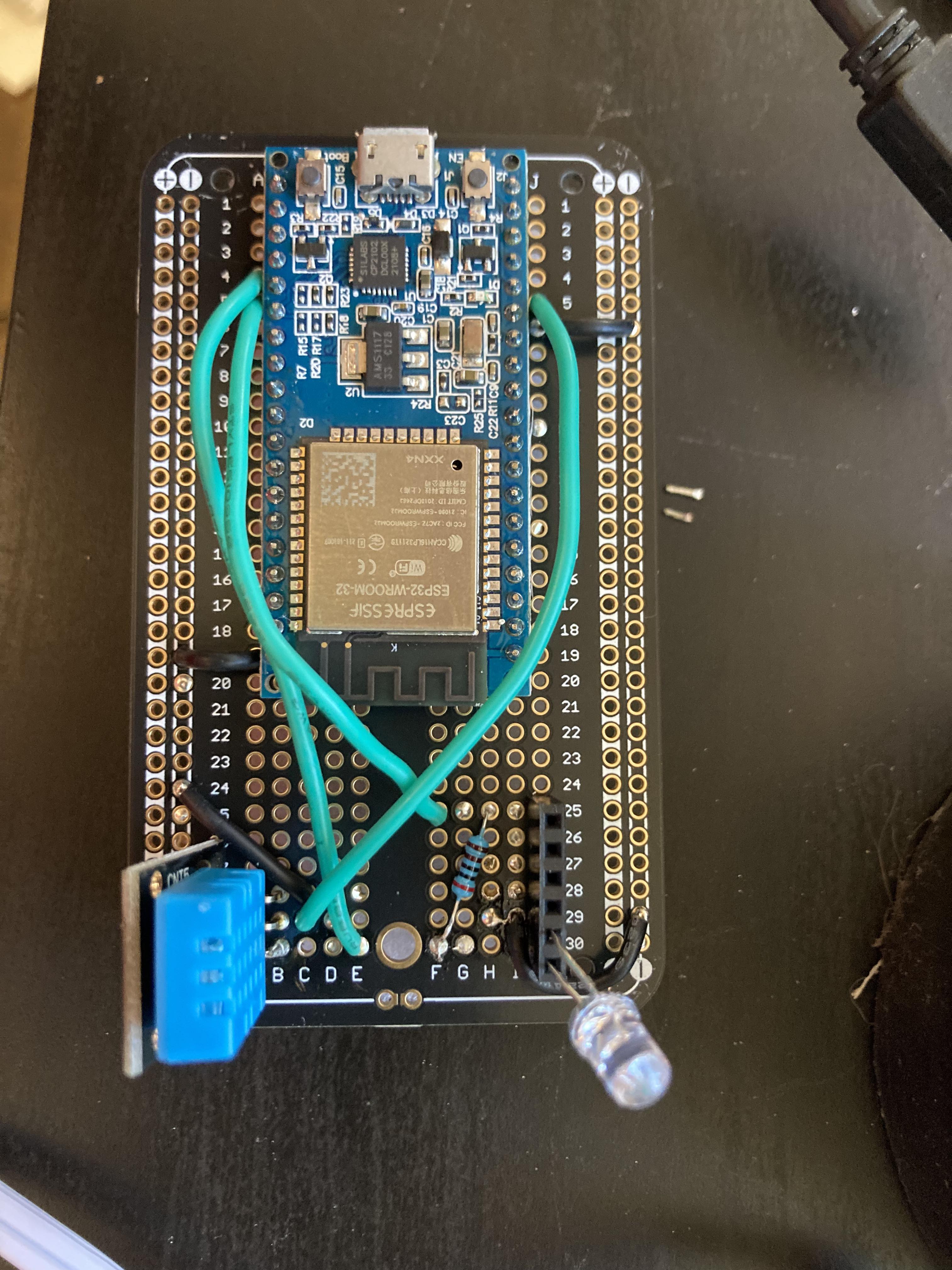

Using the same configuration as outlined in the initial ESP32 post, I carefully soldered the components onto the Protoboard. The result was a significant improvement in the consistency of the sensor readings, eliminating the previous contact issues. Below are images of the completed soldering work:

- Top View:

- Bottom View:

Electrical Safety

After completing the soldering, I was concerned about the potential for short circuits if the board was placed on a conductive surface. To mitigate this risk, I checked the conductivity of a glue gun stick I planned to use for insulation. Confident in its suitability, I applied hot glue to the entire bottom of the board. I opted for large, removable globs of glue rather than thin layers to facilitate easy removal if needed. Here is the “final” product after applying the hot glue:

Incorporating the Verter Buck-Boost Module

To extend the operational time of the ESP32 setup, I integrated the Verter buck-boost module from Adafruit along with their 4 AA battery pack. This configuration achieved an approximate runtime of 28.2 hours, which exceeded my expectations. I attribute part of this efficiency to the removable LED socket used for data transmission checks. The green LED was bright enough to disturb sleep in a darkened room, so I removed it during overnight testing. I estimate that it would have run for 20 ish hours with the LED on as that’s what I roughly estimated(the peak sensor reading plus transmission reading on my power bank may have been off….).

What is a Buck-Boost Module

A Buck-Boost Module is a type of DC-DC converter that can step up (boost) or step down (buck) an input voltage to a desired output voltage. This functionality is particularly useful in battery-powered projects where the input voltage can vary significantly as the battery discharges. The module ensures that the device receives a stable voltage, enhancing the reliability and efficiency of the system.

The Verter buck-boost module from Adafruit is a versatile power supply solution that can accept input voltages ranging from 3V to 12V and output a consistent 5.2V voltage, making it ideal for various applications. It is equipped with multiple safety features, including over-voltage protection and thermal shutdown, to ensure the safe operation of your electronics. I went with Adafruit over many companies on Amazon as a sensor failing is a disappointment whereas everything on my board being fried is infuriating. The output voltage of the Verter on the USB side is 5.2V and it is far better as a buck converter than a boost converter. Note that it uses a TPS630630 boost converter from TI and the USB connector can output 500mA according to the datasheet. The module overall can output ~1.0+A so if push comes to shove I can always adapt it if I need more current. It has 90+% operating efficiency in some cases and the efficiency graphs are below:

Efficiency vs. Output Current:

Efficiency vs. Input Voltage Current:

We see that at V_Out = 4.8V and V_Out = 5V we have an efficiency near or above 90% and that’s good enough for me.

I ensured all voltages were within specification and verified the output using an opened USB cable. Here’s the setup with the Verter and battery pack:

Once I tested everything it was fairly straightforward to throw some NiMH Ikea batteries at 1.2V 1900mAh and double check the output voltage to make sure I was ok. Moving forward I would definitely opt for Adafruit’s 8 battery pack but 4 batteries works for my purposes for now. Verter + battery pack below, note that there are some screws you gotta tighten down on for your (+)/(-):

Future Improvements

Implementing a battery monitoring system would enhance the project’s robustness, allowing for better power management. Additionally, incorporating a solar charging circuit could provide a sustainable power solution by using solar energy during the day to charge the batteries and running the device on battery power at night.

Adding OLEDs

Funny enough this tidbit actually predates the battery pack and Buck Boost Converter, but I felt that stabilizing the circuit and getting battery power working was of far higher importance than slapping a screen in the circuit.

The OLED display used is a simple 128x32 screen, acquired affordably from Amazon. Using the SSD1306 library to interface with the OLED is straightforward. My plan is to create an ESP32 GitHub repository containing all the sensor integrations packaged into a single, comprehensive folder of Python files for ease of use. This approach simplifies the process compared to tracking down and adapting various libraries.

Below are example circuits using standard SCL and SDA connections on the ESP32, as well as alternative connections by assigning the 14 and 13 pins to SCL and SDA respectively:

- 1 OLED:

- 2 OLED:

Alternative Pin Configuration

It’s essential to note that the ESP32 allows for flexible pin assignment for the SDA (Serial Data Line) and SCL (Serial Clock Line). Here’s a table showcasing the alternative pin assignments:

| SDA | SCL |

|---|---|

| 4 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 |

| 17 | 16 |

| 18 | 17 |

| 19 | 18 |

| 23 | 19 |

| 25 | 23 |

| 26 | 25 |

| 27 | 26 |

| 32 | 27 |

| 33 | 32 |

Additionally, there are input-only pins: 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, and 39.

Initializing and Testing the I2C Bus

Ideally one would connect their peripheral then run the following code to ensure that they are getting a reading from their device(change pin numbers!):

Code

from machine import Pin, SoftI2C

import time

# Initialize I2C with default pins

i2c = SoftI2C(scl=Pin(22), sda=Pin(21))

def scan_i2c(i2c):

print("Scanning I2C bus...")

devices = i2c.scan()

if len(devices) == 0:

print("No I2C devices found")

else:

print("I2C devices found:", len(devices))

for device in devices:

print("Decimal address:", device, " | Hex address:", hex(device))

while True:

scan_i2c(i2c)

time.sleep(5)Going back to the OLEDs… After we verify that they are connected correctly we can run the following to print:

Code

from machine import Pin, SoftI2C

import ssd1306

from time import sleep

# ESP32 Pin default

i2c = SoftI2C(scl=Pin(22), sda=Pin(21))

# ESP8266 Pin default

#i2c = SoftI2C(scl=Pin(5), sda=Pin(4))

oled_width = 128

oled_height = 32

oled = ssd1306.SSD1306_I2C(oled_width, oled_height, i2c)

# Clear the display buffer

oled.fill(0)

oled.text('Existence is a prison', 0, 0)

oled.text("prison.I'm bound.", 0, 10)

oled.text('to this device', 0, 20)

oled.show()

# ESP32 Pin assignment

i2c_2 = SoftI2C(scl=Pin(14), sda=Pin(13))

# Clear the display buffer

oled2.fill(0)

oled_width = 128

oled_height = 32

oled2 = ssd1306.SSD1306_I2C(oled_width, oled_height, i2c_2)

oled2.text('Existence is a prison', 0, 0)

oled2.text("prison.I'm bound.", 0, 10)

oled2.text('to this device', 0, 20)

oled2.show()The SSD1306 Library

An OLED works by emitting light from organic compounds that emit light when an electric current is applied. This technology allows for bright, clear displays that are highly efficient and have excellent contrast ratios. OLEDs are used in a variety of applications, from small displays on microcontrollers to large television screens. I direct you to the wikipedia article at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OLED if you want to do a deep dive into materials of construction, operating principle, etc.

The SSD1306 library is a widely used library for controlling OLED displays based on the SSD1306 driver. This library simplifies the process of communicating with the OLED and provides a set of functions to easily draw text, shapes, and images on the screen. By using the SSD1306 library, developers can quickly integrate OLED displays into their projects without needing to understand the low-level details of the communication protocol.

Beyond simple text one can draw lines, rectangles, circles, and even bitmaps. This allows for the creation of detailed and informative graphical interfaces provided you have enough pixels.

Future Improvements

Several quality of life improvements can further enhance the ESP32 environmental monitor. Implementing a battery monitoring system would provide better power management. Additionally, incorporating a solar charging circuit could offer a sustainable power solution by using solar energy during the day to charge the batteries and running the device on battery power at night. The design of the air intake box, sensor sampling rates, and minimizing power draw would constitute some one off things I’ll need to do, but for right now they aren’t too relevant. In any case, being able to quickly visualize what’s going on with the sensors is cool enough, but having the web interface is far more useful.

Conclusion

Through some careful(haphazard?) soldering I got a reliable temperature/humidity sensor working with a web interface and a fairly large battery capacity. One note for portability: If I ever wanted to remotely log data to Google/etc I would need to set up a hotspot and assign that as an alternative WiFi that tries to connect if the first one isn’t present.

This post is definitely a bit more stop and go than previous posts owing to the fact that I needed to document this mini project, but also have a fair bit of backlog when it comes to writing. At a later date I may revisit this and clean up the writing. The key focus is being able to reference this in the future for my own personal use.

Stay tuned for more updates.